Architectural monuments of medieval Kyrgyzstan uniting the best achievement of building techniques, architecture and decoration of that time play a great part in Central Asian history of architecture. The 11th-12th centuries are a golden age of the Karakhanid kaganat’s architecture which is presented by survivor minarets and mausoleums. The most talented architects and artists took part in the creation of these cult buildings. In the 14th century in separate regions of Kyrgyzstan, a century later after the Mongolian invasion, only not large non-nomadic agricultural settlements remained, where some revival of court and temple construction took place.

The monuments, survivor in the republic’s territory, testify that medieval architects had high building skills, knew methods of making of rich and various architectural decor. Among architectural buildings, interesting of their ornamental decoration, we cannot mention the Burana minaret (the 11th-12th cc., near Tokmak town), Uzgen mausoleums and minaret (the 11th-12th cc.), the mausoleums of Shach-Fazil (the 11th-12th cc., the Alabuka district) and Manas (the 14th c., near Talas town). The architectural ornament, fulfilled by brick laying, carving on terracotta, ganch and stucco, decorates these minarets’ bulks, facades and interiors of the mausoleums. The ornament of the medieval monuments includes vegetable, vegetable geometrical, geometrical, geometrical vegetable and epigraphic motives.

Vegetable and vegetable geometrical motives are presented by “wave” with curls, round and many-petalled rosettes rosettes, palmettos, “spring” ornament, medallions and shamrocks. “Wave” with curls is the most wide-spread pattern, which we can find in the carved terracotta of the Burana mausoleum № 1, in the facade of the Uzgen southern mausoleum and facing plates of the Manas mausoleum (Ill. 1, 1-3). A version of “wave” with curls, carved on terracotta plates of the Manas mausoleum, is especially graceful. The motif is showed as a narrow border filled in a thin running stem with big spiral curls, which have leaves at their ends. The initial point is a flower with four three-petalled (along diagonal) and four pointed leaves (along axis) (Ill. 1, 2).

This type of decor, getting the name “islimi”, is well-known in medieval architecture of settled agricultural population of Central Asia, in the kinds of applied art of Chach, Sogd and Near East [16, p.108]. “Wave” with curls has close analogies with vegetable motives on the Chuy valley’s dostarkhans of the 6th-10th centuries and a schematic image of a running vine on the Yenisei Kyrgyzes’ metallic handicrafts of the 9th-12th centuries [7, p.146, ill.1, 1-3; 5, p. 55-57]. In a new period the ornamental motif was often used in the embroidery and jewelry art of Kyrgyzes, Kazakhs, Uzbeks and Tadjiks [15, p. 83, 120-121; 6, p. 27; 12, p. 121, 139; 8, ill. 5-6].

Different types of round and many-petalled rosettes, palmettos and shamrocks decorate carved terracotta of the Burana mausoleum № 1-2, ganch-carving of the interior of the Shach-Fazil mausoleum and facing plates of Manas mausoleum’s facades (Ill. 1, 4-7, 11-15). Let’s fix our attention on ornamental patterns, survivor in the interior of the Shach-Fazil mausoleum, a wonderful monument of architecture. Vegetable flower motives are on the interior’s panel, wide ornamental belt, large frise’s borders and tiers of the mausoleum’s belts. Sixteen round rosettes of the wide ornamental belt strike of their inexhaustible art fantasy. Eight of them are fulfilled by relief carving with inscriptions along circle, the others – by graphic carving with smooth rings along circle without inscriptions. Geometrical motives are also presented in the relief rosettes against the background of little curls and leaves. The composition looks very effective thanks the rosettes’ colour drawing: ornamental strips are coated with a blue paint in the centre and with a white paint along their borders. Three round rosettes, having the form of an open bud of lotus, draw attention to themselves (Ill. 1, 4-6). In the art of Sogdians, ancestors of modern Tadjiks and Uzbeks, this flower was a symbol of the thoughts’ cleanness [9, p. 10-11].

The interior’s panel of the Shach-Fazil mausoleum is adorned with three-striped ribbon, whose background is filled in spiral sprouts and leaves fulfilled by graphic carving. On the upper projection of the frieze we can see borders with an original image. The borders’ carving has complicated patterns and jewelry fulfillment: complicated ornamental compositions consist of spiral elements, round and many-petalled rosettes, circles, united by lines, rhombs, zigzags, crossing lines (Ill. 1, 8-10).

Among the borders of the monument’s interior a belt with so-called “spring” ornament, which consists of crossing squares and united half-circles with shamrocks, has a great interest (Ill. 1, 16). The belt with this ornament is situated on half-arches, round rosettes in the technique of relief carving are in the tympanums’ corners of the mausoleum. Ornamental figures, including a round medallion with curls and pointed square with a half-moon, are carved in the centre of the sails’ segments [9, p. 12-13].

The round rosettes, medallions, ornamental borders of the Shach-Fazil mausoleum date back to Central Asian architectural traditions of the 6th-8th centuries [16, p. 146]. Some vegetable geometrical motives of the mausoleum find their parallels in the decor of the Juma mosque in Khiva and a palace of Khulbuka of the 10th-11th centuries. However patterns of medallions and rosettes, which decorate the Shach-Fazil mausoleum, have no exact analogies and by this reason scientists made a conclusion about their local origin [9, p.28].

The motif “eight-petalled rosette” was used in the decor of the arch’s tympanums, square tiles of the portal and corner columns of the Manas mausoleum. The rosette is an interlacement of four figures in the form of hearts with shamrocks inside (Ill. 1, 12).

In the facade of the Manas mausoleum palmettos consisting of five leaves are repeated by a couple in two adjacent version. The motif was used in the framing of the building’s portal, in the facing of portal arch, in the panneau and horizontal borders of walls (Ill. 1, 14-15). Number of shamrocks and palmettos, which alternate between themselves, are represented in a few versions and decorate of the mausoleum’s tympanums [13, p. 72-74, 77].

Many-petalled rosettes, palmettos and shamrocks have much in common with motives on the glazed ceramics of Samarkand and the Yenisei Kyrgyzes’ metallic handicrafts of the 9th-12th centuries [20, ill. 26, 30, 31, p. 118, ill. 8; 5, p. 55-57]. The same motives were wide-spread in the embroidery and jewelry art of Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Uzbek and Tadjik [15, p. 83-84, 120-121; 6, p. 25; 12, p. 122-123; 8, ill. 5, 7].

According to creeds of Central Asian farmers, “wave” with curls, palmettos and complicated rosettes were connected with Navruz, a New Year holiday, and personified of the nature’s awakening [20, ill. 62, 73].

Geometrical and geometrical vegetable motives are also very diverse in monumental architecture of the 11th-14th centuries: “chess check”, cross figures, meandrous, guilloche, swastika, star, rhomb, square and circle (Ill. 2). The motif “chess check” decorating facing tiles of the portal of the Manas mausoleum was known in high antiquity (Ill. 2, 1). This motif is analogous to a pattern on the decorated ceramics of the Anau culture of the 4th-2nd millenniums B.C. and an early non-nomadic burial of the Anay valley of the 6th-4th centuries B.C. [16, p. 21, ill. 1; 7, p. 70, ill. 1, 1]. “Chess check” is present on wooden vessels of the Tashtyk (Early Kyrgyz) culture of the 1st-5th centuries and has much in common with quadrangular motif on the Yenisei Kyrgyzes’ “vases” of the 6th-8th centuries [5, p. 137; 22, p. 27-28].

Except the main version of the motif in the Manas mausoleum, in the monument’s facade “chess check” includes squares, which alternate in straight and diagonal arrangement. In a new period the ornamental motif having names “chymyn kanat” and “shybynkanat” (the fly’s wings) was used by Kyrgyzes and Kazakhs in mats of reed [18, table. XXXV, 11].

Cross figures are not isolated from the other ornamental motives. In one of the versions cross enters into rhomb as in the carved terracotta of the portal of the Uzgen southern mausoleum; in another one cross creates a geometrical composition with rhomb and square that we can see on terracotta plates of the Manas mausoleum’s facade (Ill. 2, 2, 12). It is also interesting a geometrical composition in the facing of corner columns of the Manas mausoleum. The ornament consists of cross figures, situated between eight-beam stars, which include eight-petalled rosettes [13, p. 74].

Meandrous, guilloche, star, square and circle are wide-spread in ornamental belts of the Uzgen and Burana minarets, carved bricks and stucco of the Burana and Uzgen mausoleums, and also in facing plates of the Manas mausoleum (Ill. 2, 3-15).

Different types of meandrous, which decorate ornamental belts of the Burana and Uzgen minarets, are made by brick laying and well-known in Central Asian architecture of the 10th-12th centuries [10, p. 160]. For the first time in Central Asia meandrous, one of the most ancient symbols was represented on the Andronovo culture’s vessels of the 16th-15th centuries B.C. [14, p. 28, ill. 1, 2 e].

The easy motif “breaking meandrous” was used in the border of the arch’s archivolt of the Manas mausoleum (Ill. 2, 6). This type of decor, according to opinion of M.E. Masson and G. A. Pugachenkova, reminds of the motif “alamachek” (variegated plumage) from the Kyrgyz embroidery [13, p. 116].

The motif “guilloche” makes an unusual impression in the portal of the Uzgen southern mausoleum. Vertical zone of ornament is formed by curve crossing of lines, which create swastikas and circles with many-petalled rosettes inside (Ill. 2, 8). The Uzgen middle mausoleum gives an example of another interpretation of guilloche. Artists made of crossing lines an ornament including four-petalled rosettes with cross inside (Ill. 2, 7). Spiral shoots and leaves fill in free places between rosettes [10, p. 94, 77].

The motif “swastika” made by brick laying on the plinth of the Burana minaret has a likeness with the Kalyan minaret of the 12th century (Ill. 2, 9). There exist lots of meanings of this ancient symbol, but they are positive for the greater part of people. For example, swastika is interpreted as a symbol of sun and favourable events in pre-buddhistic ancient Indian and some other cultures [3]. Before the Great Patriotic War swastika was an ornamental motif of Central Asian people, in particular in the embroidery of Kyrgyzes and Kazakhs.

The motif “star” is represented in the soffit’s facing of the portal of the Uzgen northern mausoleum and on walls of the Manas mausoleum (Ill. 2, 10, 11). There are graceful eight-beam stars united with a background of vegetable ornament in the decor of two buildings. In the Manas mausoleum star has four-petalled rosettes incide. We can find an exact analogy for this type of pattern in caved ganch of Aisha-Bibi of the 12th century (Taraz city) (Ill. 2, 11). Later on geometrical compositions of stars are used often in ganch-carving and facings of bricks in the caravanserai of Rabat-i-Malik, Magoki Attari and Shah-i-Zindeh [10, p. 86-87]. Nowadays star motives (girikhs) consisting of combinations of different polygons with many-beam stars belong to chief types of architectural decor of Uzbekistan and Tadjikistan.

In wide ornamental belts of the Uzgen minaret an ornament in the form of rhombs, which have a cross figure inside, was made by brick laying. In the facades of the Uzgen mausoleums we can find the same rhombic drawing (Ill. 2, 2).

Unlike simple circle in the carved terracotta of the Burana mausoleums № 1-2, the pattern is the centre of an ornamental composition in facing tiles of the Manas mausoleum (Ill. 2, 14, 15). The circle is united by loops from above and below, and its sides are transformed in four-petalled rosettes, which have a half of a twelf-petalled flower in. Two repeated branches with curved leaves and a six-petalled flower are represented in the frame [10, p. 161; 13, p. 76].

Rhomb, square and circle are well-known on the ceramics and leathern handicrafts of the 1st-5th centuries, bone details of arrows’ cover and iron harness of Yenisei Kyrgyzes of the 6th-8th centuries [11, p. 62, ill. 22; 21, p. 115, table. XXXVII]. Cross figures consisting of ornamental compositions of medieval monuments of Kyrgyzstan have their analogies in the glazed ceramics of Sogd, Otrar and Taraz of the 11th-13th centuries [23, table. XLIII; 19, p. 190, table. XII, 25; 1, p. 112, ill. 68, 7, 14]. Scientists suppose that circle, rhomb and cross are the most popular symbols of sun in traditional art of the all people of earth. Afterwards these ornamental motives became wide-spread in many forms of Kyrgyz and Kazakh applied art.

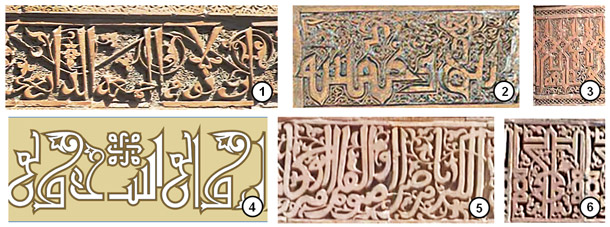

Epigraphic motives represent distorted good wishes and have first of all decorative meaning. These motives fulfilled by the handwritings “naskh” and “kufic” decorate facades of the Uzgen and Manas mausoleums, and also the interior of Shach-Fazil mausoleum (Ill. 3). The epigraphic decor with geometrical and vegetable elements create rich and fantastic ornamental compositions in the architectural monuments. In the portal of the Uzgen northern mausoleum epigraphic inscriptions of the handwritings “naskh” and “kufic” are united harmonically. The inscription by the first handwriting fulfilled in carved terracotta gives dynamics to a portal niche, and the frieze’s ornament with the handwriting “kufic” has a calm character (Ill. 3, 1,2).

Medieval artists used the complicated handwriting “flourishing kufic” in the portal of Manas mausoleum. Winding stems and leaves go from letters with the inscription “al-mulk”, and on the left side we can see a stylized lotus flower. The epigraphic decor of Shach-Fazil mausoleum also came organically into the architectural art conception [10, p. 84-85; 13, p. 76].

In conclusion it is important to note that these vegetable, geometrical and epigraphic motives have numerous parallels in Central Asian architecture by their technique’s fulfillment and stylistic peculiarities. The motives are mostly like to the decor of the Krasnaya Rechka site’s dwelling complex, a madrasah in the Shah-i-Zindeh ensemble, architectural monuments of Maverannakht and Khorasan. Moreover, the analysis of the architectural decor in medieval Kyrgyzstan’s monuments showed that lots of geometrical patterns (“chess check”, rhomb, square, circle, meandros, etc.) date back to antiquity, and the architectural ornaments of minarets and mausoleums are a harmonic synthesis of settled agricultural and nomadic cultures. The architectural decor’s parallels of medieval Kyrgyzstan with Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Uzbek and Tadjik ornaments of a new period demonstrate stability of many vegetable and geometrical motives, and also confirm existence of long cultural historic connections among the modern people’s ancestors of Central Asia. A millennium later the architectural buildings of Kyrgyzstan of the 11th-14th centuries did not lose their great historic and art value and became a common cultural property of Central Asian people.

Table 1. Растительные и растительно-геометрические мотивы в декоре архитектурных памятников Кыргызстана XI-XIV вв.:

1-3 – «волна» с завитками (по В.Д. Горячевой, 1983 и Д.Д. Иманкулову, 2005); 4-6 – круглые розетки (по Д.Д. Иманкулову, 2002); 7-10 – бордюры с многолепестковыми розетками, спиралевидными побегами и геометрическими фигурами (Д.Д. Иманкулову, 2005); 11-13 – многолепестковые розетки (по В.Д. Горячевой, 1983 и М.Е. Массону, Г.А. Пугаченковой, 1950); 14 – пальметты; 15 – пальметты и трилистники (по М.Е. Массону, Г.А. Пугаченковой, 1950); 16 – «пружинный орнамент».

Table 2. Геометрические и геометрическо-растительные мотивы в декоре архитектурных памятников Кыргызстана XI-XIV вв.:

1 – «шахматная клетка»; 2 – крестовидные фигуры и ромбы; 3-5 – меандр; 6 – «разорванный меандр» (по М.Е. Массону, Г.А. Пугаченковой, 1950); 7,8 – плетенка; 9 – свастика; 10,11 – восьмиконечные звезды с цветочно-растительными мотивами; 12 – восьмиконечные звезды с многолепестковыми розетками и крестами; 13 – соединенные квадраты и кресты; 14 – кружковый мотив (по В.Д. Горячевой, 1983); 15 – круг с цветочно-растительными мотивами (по М.Е. Массону, Г.А. Пугаченковой, 1950).

Table 3. Эпиграфический декор архитектурных памятников Кыргызстана XI-XIV вв.:

1-6 – эпиграфические мотивы.

1. Акишев К.А., Байпаков К.М., Ерзакович Л.Б. Древний Отрар. – Алма-Ата, 1972

2. Антипина К.И. Особенности материальной культуры и прикладного искусства южных киргизов. – Фрунзе, 1962.

3. Багдасаров Р.Свастика: священный символ. Этнорелигиоведческие очерки. - М., 2001

4. Вадецкая Э.Б. Таштыкская эпоха в древней истории Сибири. – СПб., 1999.

5. Грач А.Д., Савинов Д.Г., Длужневская Г.В. Енисейские кыргызы в центре Тувы (Эйлиг-Хем III как источник по средневековой истории Тувы). – М., 1998.

6. Джанибеков У.Дж. Культура казахского ремесла. – Алма-Ата, 1982.

7. Древний и средневековый Кыргызстан. – Бишкек, 1996.

8. Ершов Н.Н. Каратаг и его ремесла. – Душанбе, 1984.

9. Иманкулов Д.Д. Мавзолей Шаха-Фазила – выдающийся памятник раннеисламской архитектуры Кыргызстана. – Бишкек, 2002.

10. Иманкулов Д.Д. Монументальная архитектура юга Кыргызстана XI – XX вв. – Бишкек, 2005.

11. Кызласов Л.Р. Таштыкская эпоха в истории Хакасско-Минусинской котловины (I в. до н. э. – V в. н. э.). – М., 1960.

12. Кустарные промыслы в быту народов Узбекистана ХIХ – ХХ вв. – Ташкент, 1986.

13. Массон М.Е., Пугаченкова Г.А. Гумбез Манаса. – М., 1950

14. Муканов М.С. Казахские домашние художественные ремесла. – Алма-Ата, 1979.

15. Народное декоративно-прикладное искусство киргизов. ТКАЭЭ. – М., 1968, т. V.

16. Ремпель Л.И. Архитектурный орнамент Узбекистана. История и теория построения. – Ташкент, 1961

17. Ремпель Л.И. Цепь времен: Вековые образы и бродячие сюжеты в традиционном искусстве Средней Азии. – Ташкент, 1987.

18. Рындин М.В. Киргизский национальный узор / Вступ. статья А. Н. Бернштама. – Л.-Фрунзе, 1948.

19. Сенигова Т.Н. Средневековый Тараз. – Алма-Ата, 1972

20. Ташходжаев Ш.С. Художественная поливная керамика Самарканда IX – начала XIII вв. – Ташкент, 1967.

21. Худяков Ю.С. Вооружение енисейских кыргызов VI-XII вв. – Новосибирск, 1980.

22. Худяков Ю.С. Кыргызы на Табате.– Новосибирск, 1982.

23. Шишкина Г.В. Глазурованная керамика Согда (вторая половина VIII - начало XIII вв.). – Ташкент, 1979.